-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Six years old. “Use both hands to hold the camera!” Click!

Eight years old. “You need to hold your breath when you’re pressing the shutter button; you don’t want the picture to turn out blurred, do you?” Click!

Twelve years old. “Look at this picture here you took during our vacation. Why cut me off at the knees? And this one here. Why isn’t your brother at the center?” Click!

Photography has always been a part of my life. Always. My dad, an ardent fan of anything artsy, was the main reason for it. He is a photographer, a painter, a musician, and an architect. As a father of two, he encourages his only pair of kids to pursue the same path…well, not exactly. Neither my brother nor I am an architect. But we are both taught to appreciate arts since a very young age. My brother chooses drawing and animation, I choose photography and music. Art is beautiful. Art is the best way to put one’s self out there into the world. Photography, a form of realist art, is the best way to capture one’s self.

Unlike Roland Barthes, I do see myself as an amateur photographer. He does not for he is “…too impatient for that: [he] must see right away what [he has] produced” (Camera Lucida, pg. 9). Since he is not a photographer, Barthes recognizes the need for one in order for him to even begin scrutinizing a photograph. Thus, for a photograph to be produced, two important entities are required: the Operator and the Spectator. The experience of both the photographer (the former) and the one glancing at the photograph (the latter) is too different to be talked about together. Barthes, a Spectator, is more interested in explaining the feeling one experiences when looking at a photograph whereas I, an Operator, definitely lean more towards “…the emotion [that] had some relation to the “little hole” through which [I] look, limit, frame, and perspectivize when [I] want to ‘take’” (Camera Lucida, pg. 10). For acknowledging this distinct feature of photography in his effort to dissect its true meaning in relation to one’s self, Camera Lucida certainly fits its own title as a book on the ‘Reflections on Photography’.

Photography is an amazing way for one to capture an emotion and also for one to materialize a feeling that has been building up. In simpler terms, photography is a perfect means for people to express the identity without having to put it into words. But then again, photography is not the only way to do so. After music, painting is the next best thing to be considered a universal language. And of all the paintings I have encountered in my life, this is one of my least favorite:

Tarian ©

This painting is basically of three unknown figures dancing happily together. It is a painting called Tarian (dance) by an unknown artist to most. Even though it is not a photograph, I do see it somewhat in a way that most view photography. For starters, there are distinguished objects in the painting which include the three dancers in red, the tall grass, and the clear, cloudless sky. To think about it, one could even consider those as the studium* of the painting. A studium to me is whatever one can see in an artwork that represents the setting, whereas a punctum** is the something that stirs up an emotional response from a viewer. The punctum of this painting is obviously there, but I won’t point it out, yet. Although painting and photography, together with sculpture and cinematic art, are the same in that all of them are visual arts, a painting differs from a photograph where the studium and punctum are there on purpose. The background and the details are all created by the artist. Even if a photographer intentionally chooses his subject, the subject in itself is real. In contrast, whatever is in a painting has to be thought of first before it could be produced on a canvas.

The main thing, however, that needed to be stressed about Tarian are the three figures in a dancing pose that viewers are instantly drawn to. In the chapter He Who Is Photographed in Camera Lucida, Barthes talked about this unique process of posing. In a sense, for him, it is quite hopeless for one to try to appear natural in a photograph for that is a definite unattainable feature of photography. This is because, in Barthes own words, “…I derive my existence from the photographer… I experience it with the anguish of an uncertain filiation: an image – my image – will be generated” (Camera Lucida, pg. 11). In other words, people unconsciously pose because they are conscious of a photograph that will be developed which will contain his or her image, thus their identity too.

An image of a person is not only about the face and the body, but also of the way his or her personality is expressed. When someone chooses to smile, it is because he wants to be associated with happiness. That is why fashion models are asked to have different expressions for different catwalks; not all fashion shows are about feelings of contentment. Even when a person is supposedly not posing for a picture, that is the identity he wishes to portray – one of impatience. Similarly, when an artist paints, especially that of human beings, he is indirectly putting them in poses since no such thing as a natural form exists in the first place to painted figures. In Tarian, although one cannot make out the facial expressions, the fact that these figures are in a dancing posture helps viewers form a mental image of the self that is being portrayed. Every artwork in this world has a purpose, and the purpose of this painting is for the artist to express his feeling of ecstasy to the world hence the dancing postures.

According to Barthes, the pose which one puts up when in front of a camera is not to be mistaken for one’s true “self”. A person’s self is too complicated and too dispersed to be caught in a moment. Instead, the character that is developed on paper is “…heavy, motionless, [and] stubborn…” (Camera Lucida, pg. 12) since it could not progress with time the way that the self does in real life. As in the case of Tarian, the artist painted those figures in that particular manner because he wants those characters to vibrate the joy and merriment of being in one another’s presence; it has nothing to do with the painter’s self except that of what he felt during that specific moment. A single moment of delight in his life could never do justice to the artist as a person since there are more angles to his personality than just what is obvious in a painting.

Likewise, in the real world, it is impossible for a person to put his entire self out in the open when confronted by unfamiliar faces in an unknown environment. Nobody can depict an entire self to those he had just met except, of course, if he decides to scream his likes and dislikes for others to take note of. Because of that, one needs to pose differently for different occasions. Therefore, it should be understood that this idea of posing is not exclusive to artworks as every person on earth is known to have posed, especially when in the presence of the mass public. Some call it a facade. Nevertheless, the concept is still the same. As how Barthes wants his picture “…to ‘come out’ on paper…endowed with a noble expression…” (Camera Lucida, pg. 11), so does a person wishing to make a solid good first impression with his fellow human beings. It is nothing to be ashamed of. Posing, or wearing a mask, does not imply an absence of identity but simply portrays the side of a person that he wants to be associated with. For that reason, the Spectator should not take for granted and conclude a person’s identity based on a single pose, but at the same time it is important to recognize a pose as part of a person’s wider identity.

Yet, as a photographer myself, I hate it when people start to strike a pose whenever they see me holding a camera. True, I understand their concern of wanting the photograph to look ‘good’ but honestly, an ‘ugly’ picture could even turn out more beautiful if they just give it a chance. As mentioned, what excites the Operator is the vision framed by the keyhole. Therefore, a thought-of pose could never be exciting to the photographer. I am not interested in the product so much as what is in front of my eyes. If a friend is twirling in happiness, that will be my target object regardless of how her hair would look like in the picture or how distorted her body would appear. In Photography as Adventure, Barthes talks about how a photograph is only considered a photograph if it stirs a feeling of adventure in him. My sense of adventure, however, comes not from looking at a photograph but from the real life experiences that I try to capture on camera – objects in motion. For me, that is beauty. That is truth.

But since I have no control over a painting that is not done by me, I cannot talk about Tarian the same way I would a photograph I personally took. Yet, Tarian is a painting that has always caught my attention. I do not like it, but honestly, I have always found it interesting. Although the motion is not one of extreme movements (the kind that I usually love to capture on camera), it is in the simplicity that I found the adventure. Borrowing Barthes’ term, that painting advenes. It attracts my attention. How so? Although Tarian is one of my least favorite paintings, I find it fascinating not because of its punctum, but of the fact that three faceless figures could exert such strong emotions to its viewers. As individuals living in a society, we have always been taught by our culture that the face – especially the eyes – is the window to human emotions. Facial expression is important as part of our everyday non-verbal communication. But as we see here, that is not the case. Colors and lines constituted the human figures that are interpreted as dancing, hence joy. No eyes or mouth, just lines. And just like Barthes, I do not believe in lifelike photographs but if “…it animates me [then] this is what creates every adventure” (Camera Lucida, pg. 20). This best explains why this simple and lifeless painting brings about such a strong reaction from me for it brings out a consciousness within.

Alongside advene, Barthes is interested in Photography for sentimental reasons. He puts it best when he said, “I see, I feel, hence I notice, I observe, and I think” (Camera Lucida, pg. 21). Since I have evaded announcing the punctum to Tarian for a while now, I feel it is time for me to do so. Back when I was a young Spectator, years ago, the punctum to the painting had been, and in fact still is, the signature at the bottom right corner. That is the signature of my dear father. Yes, Tarian is painted by my father. For being the daughter to the artist, I have a firsthand knowledge about the story behind the painting: the figure on the left is him, my dad; the one on the right is my mother; the smaller figure in the middle is my brother. Me? I am not in the painting. This artwork was done way back before I was born. Actually, it was started even before my brother was born. But right after he came into the world, he was quickly added as the third figure. The question now is, why wasn’t the same done for me? When asked, this was his answer: “After you were born, your mum asked me to stop painting so that I could focus more on the family.” Noble indeed, but what about my sense of belonging? I do not like Tarian for the sake that I was not included in it. Narcissistic, maybe, but hey, I am part of the family, aren’t I? This is the sentimental reason behind Tarian being my least favorite painting by him. This punctum of his signature is the “…something [that] has triggered me, has provoked a tiny shock, a satori, the passage of a void” (Camera Lucida, pg. 49). This painting reminds me that there was actually a time when I was not yet born but the History of the world does not stop to exist in my knowledge.

Barthes wrote about History being the time when his mother was alive before him in History as Separation: “Thus the life of someone whose existence has somewhat preceded our own encloses in its particularity the very tension of History, its division” (Camera Lucida, pg. 65). This division in History is noted in the photograph of his mother wearing clothes no longer worn in his period. Obviously Barthes was not talking about History in the sense of human being’s gradual transformation from past to present – History is seen in this context as a personal transformation. As History is seen to be divided between two existences, the moment one passes a second, that last second becomes History as it ceases to exist. This is described further by Barthes when he points out that the living soul is the only thing contrary to History. And so, in relation to time, a person’s identity is not easily defined as it could already be ‘History’ when it is talked about. A person may have a certain interest when he was in his 20s but what about twenty years later? Or thirty years later? Who is going to say that the person will not evolve? This, however, is the beauty of one’s identity. Nobody can pinpoint it. Nobody can really say, “I am this, you are that.” People change and a photograph is just a document that holds evidence to a person’s self at a particular point in his life.

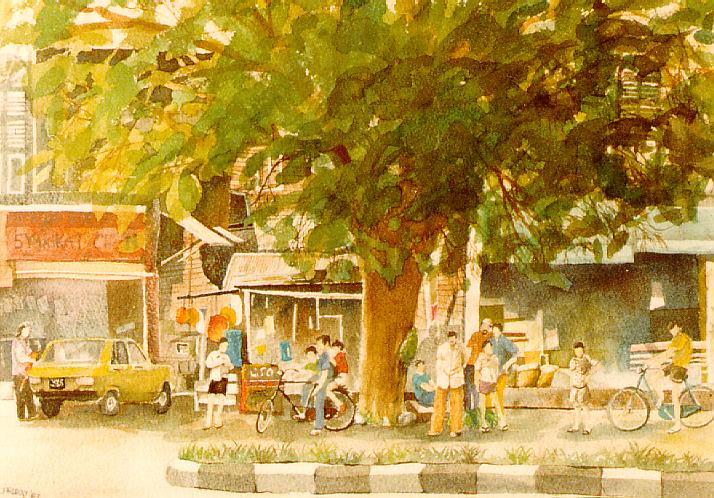

Pekan ©

Given my opinion on the painting Tarian, it is understandable for one to assume that my favorite painting by my father would be one done after 1989, the year I was born. However, Pekan (town) is actually one of those paintings which I used to stare at a lot when I was younger. For some reason, my father is not too proud of this one. In our old house, this canvas was nailed at a corner where no one except family members would usually passed by. In other words, this painting is almost invincible, even to me after a while. But once in a blue moon, I would sit upside down on the couch where this painting was hung above, and stared at my father’s recollection of his past. Those small figures are supposed to be him and his friends (including his then-girlfriend, my mother) and the scene, or studium, is of them having cendol – a Malaysian dessert – under a tree where the hawker has his stall. But unlike the first painting, the punctum of Pekan is not my father’s signature at the bottom left corner. Even though this painting was finished in 1986, I love it anyway because the overall scene of those young architecture students reminds me that my parents were once young too, and I am certainly not the first person in the family to have such strong patriotic feelings over my fellow countrymen.

The punctum to me in this painting is the name of the store furthest left: Syarikat Chan (Chan Company). Chan is a Chinese surname, and in this painting, it is the only legible element of it. My father has no problem acknowledging in this artwork that Chinese are advancing much better in business at a time when Malays were fighting for economic equality. This is the kind of History that I am proud of. Even if I am not part of the painting, these college students in the 80s are proofs that regardless of skin color, everyone can live side by side without beliefs, cultures, or personalities getting in the way. A person’s self may change given time, but the course it chooses to take depends on its History. In the same way, although the Malaysia of now is different from the Malaysia back then, History could be the remedy all of us have been waiting for. As mentioned, a person’s old behavior that is captured in a photograph – or painting – may not dictate him any longer, nonetheless it is still considered part of his self. History may be why I hate Tarian, but History is also why I love Pekan.

Photography, in definition, is the art of creating still pictures. It is an art – a way for the artist to appeal to the senses and emotions. Nothing more. Spectators do have the opportunity to make their own interpretations of a photograph but the real photograph lies in the view of the Operator, the photographer. The identity which the photographer chooses to capture is no more than a tiny fraction of a person’s self at a certain period in his own History. By studying a photograph one may be able to form a rough idea of that person, perhaps, but Identity, with a capital I, will never ever be successfully captured by both the amateur and professional photographers even if they try, for it is not there to be caught on camera in the first place.

*According to Barthes, studium is an application to a thing, taste for someone, a kind of general, enthusiastic commitment…without special acuity (Camera Lucida, pg. 26).

**Punctum, however, disturbs the studium as it stings, specks, and cuts (Camera Lucida, pg. 27).

Syaza Farhana Mohamad Shukri

Fall 2009